Colonies Lost and Found

27/02/2015

Professor Mark Horton, the Society President, will lead us through the archaeology of early West Country settlement of the New World

European settlements in the Caribbean began with Christopher Columbus. Carrying an elaborate feudal commission that made him perpetual governor of all lands discovered and gave him a percentage of all trade conducted, Columbus set sail in September 1492, determined to find a faster, shorter way to China and Japan. The first proper European settlement in the Caribbean began when Nicolás de Ovando, a faithful soldier from western Spain, settled about 2,500 Spanish colonists in eastern Hispaniola in 1502. The Spanish administrative structure prevailed for132 years.

European settlements in the Caribbean began with Christopher Columbus. Carrying an elaborate feudal commission that made him perpetual governor of all lands discovered and gave him a percentage of all trade conducted, Columbus set sail in September 1492, determined to find a faster, shorter way to China and Japan. The first proper European settlement in the Caribbean began when Nicolás de Ovando, a faithful soldier from western Spain, settled about 2,500 Spanish colonists in eastern Hispaniola in 1502. The Spanish administrative structure prevailed for132 years.

By the early seventeenth century Spain's European enemies, no longer disunited and internally weak, were beginning to breach the perimeters of Spain's American empire. The English and the French moved rapidly to take advantage of Spanish weakness in the Americas and over commitment in Europe. In 1625, the English settled Barbados and tried an unsuccessful settlement on Tobago. They took possession of Nevis in 1628 and Antigua and Montserrat in 1632. They planted a colony on St. Lucia in 1638, but it was destroyed within four years by the Caribs.

Meanwhile, an expedition sent out by Oliver Cromwell (Protector of the English Commonwealth, 1649-58) under Admiral William Penn (the father of the founder of Pennsylvania) and General Robert Venables in 1655 seized Jamaica, the first territory captured from the Spanish. Trinidad, the only other British colony taken from the Spanish, fell in 1797 and was ceded in 1802. Although Jamaica was a disappointing consolation for the failure to capture either of the major colonies of Hispaniola or Cuba, the island was retained at the Treaty of Madrid in 1670, thereby more than doubling the land area for potential British colonization in the Caribbean. By 1750 Jamaica was the most important of Britian's Caribbean colonies, having eclipsed Barbados in economic significance.

Meanwhile, an expedition sent out by Oliver Cromwell (Protector of the English Commonwealth, 1649-58) under Admiral William Penn (the father of the founder of Pennsylvania) and General Robert Venables in 1655 seized Jamaica, the first territory captured from the Spanish. Trinidad, the only other British colony taken from the Spanish, fell in 1797 and was ceded in 1802. Although Jamaica was a disappointing consolation for the failure to capture either of the major colonies of Hispaniola or Cuba, the island was retained at the Treaty of Madrid in 1670, thereby more than doubling the land area for potential British colonization in the Caribbean. By 1750 Jamaica was the most important of Britian's Caribbean colonies, having eclipsed Barbados in economic significance.

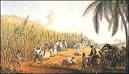

The first colonists in the Caribbean were trying to recreate their metropolitan European societies in the region "The Caribbee planters," wrote the historian Richard Dunn, "began as peasant farmers not unlike the peasant farmers of Wigston Magna, Leicestershire, or Sudbury, Massachusetts. They cultivated the same staple crop--tobacco--as their cousins in Virginia and Maryland. They brought to the tropics the English common law, English political institutions, the English parish [local administrative unit], and the English church." These institutions survived for a very long time, but the social context in which they were introduced was rapidly altered by time and circumstances. Attempts to recreate microcosms of Europe were slowly abandoned in favour of a series of plantation societies using slave labour to produce large quantities of tropical staples for the European market.

The first colonists in the Caribbean were trying to recreate their metropolitan European societies in the region "The Caribbee planters," wrote the historian Richard Dunn, "began as peasant farmers not unlike the peasant farmers of Wigston Magna, Leicestershire, or Sudbury, Massachusetts. They cultivated the same staple crop--tobacco--as their cousins in Virginia and Maryland. They brought to the tropics the English common law, English political institutions, the English parish [local administrative unit], and the English church." These institutions survived for a very long time, but the social context in which they were introduced was rapidly altered by time and circumstances. Attempts to recreate microcosms of Europe were slowly abandoned in favour of a series of plantation societies using slave labour to produce large quantities of tropical staples for the European market.

A central element of research is the use of both archaeological and documentary sources to conduct ‘historical archaeology’. The research has centred on the island cultures of the Eastern Caribbean, particularly St Kitts and

The islands are not of particular economic importance nowadays, but from the seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries they generated huge wealth, based upon plantations worked largely by slaves. This plantation ‘revolution’ was closely linked to the industrial revolution, and saw the beginnings of many institutions such as banking, insurance and industrial companies. The plantations mainly produced sugar and a range of other tropical crops such as tobacco, coffee and cocoa. A large number of the fine eighteenth-century houses in

Wotton-under-Edge Civic Centre

Friday 27th February 2015 at 7.30pm

Visitors welcome.

Non-members £5 on the door

We're on Facebook!

Wotton Heritage Centre has a facebook page so you can have rolling updates on the activities of the Historical Society, Museum and Heritage Centre.

Read More...So, What's Special About Wortley?

Dr. David Wilson of Keele University, Director of Excavations at Wortley from 1983 to 1996, gives an overview of the finding at this Roman site.

Read More...Tyndale and Venn

Hugh Phillips takes a fairly light-hearted look at their place in History.

Read More...