William Tyndale (1494 -1536)

His Life and the English Bible by Dawn Waring

There is no precise evidence as to when William Tyndale (some- times known as Hutchins) was born, but a few facts about his family in id-Gloucestershire and according to the register of the University of Oxford, where in his late teens he took his degrees, his birth is believed to have been in 1494. As o his place of birth, this remains a mystery though it is thought that he was born with- in a few miles of Dursley, west of which lies Stinchcombe where, in the early 1500s, a Richard Tyndale inherited Melksham Court from a relative, Talbot Hochyns. Richard ad two sons, Thomas, and William, who inherited jointly the property, on Richard’s death. The said William married Alice Hunt of the farm called Hunt’s Court at North Nibley, and since they had a son also called William, this gave rise to the belief that this could be William the translator, and North Nibley the place of his birth. However, the Hunt’s Court William is known to have been alive in the 1540s, years after William the translator’s death. Wherever he was born, William is believed to have been baptised in the church in North Nibley, and that as a young boy, he received his early education and grounding in Latin at the Grammar School at Wotton-under-Edge, founded in 1384 by the Dowager Lady Berkeley.

The name Tyndale suggests a northern origin, from the Tyne region of Northumberland, a letter dated 1663 from a descendant of William’s brother, Edward, claiming that the family grew from a Tyndale who came from the north during the Wars of the Roses (1455 -1485) settling in Gloucestershire where he changed his name to Hutchins for reasons of safety, only revealing his true name to his children on his deathbed. Just north of Stinchcombe lies Slimbridge where it is recorded that Edward Tyndale was granted the lease of a manor house at Hurst Farm in 1529. He was a powerful man in Gloucestershire having been appointed receiver of rents for the Berkley Estates, later holding by grant from the Abbot of Tewkesbury, the Manor of Pull in Worcester, and that of Burnet in the county of Somerset. Thus, at one time or another he had responsibilities in the three counties of Gloucestershire, Worcestershire and Somerset. His Will, proved in London in 1546, showed him to have been a man of wealth and substance. Another brother, John Tyndale, resident in London, organised the production of woollen cloth in Gloucestershire and its sale in London, and traded in leather, the bi- product of wool. By 1522, the Tyndale family had risen to positions of real wealth and power so that the notion that William came from humble origins but dared to challenge the great and powerful in London, is untrue.

In 1506, at the tender age of twelve, William went up to Oxford University where he was registered as William Hyphens, residing at Magdalene Hall. The registers record that he took his BA degree on 4th July 1512, in the same year becoming a sub deacon. He was created MA on 2nd July 1515 at which point he was able to study theology. Between 1517 and 1521, Wil- liam was at Cambridge University where he studied Divinity and Greek and became acquainted with the work of the Dutch philosopher, Desideratum Erasmus, who was lecturer there, though it is unlikely that he met Erasmus, who was away during his time there. He might even have begun his study of Erasmus’s Greek Testament at that time. On leaving Cambridge, William returned to Gloucestershire where he became tutor to the children of Sir John Walshe, who, it is recorded in 1522, had considerable wealth in goods and lands over a wide area in Gloucestershire.

It is not known when William became a priest, only that he did, records confirming that he and his brother, John, were ordained to minor orders. William began to make a name for himself as a preacher, especially at St. Aus- tin’s Green, now known as College Green, in Bristol. Although his text came from the Latin Bible, his sermons were in English. At about this time, 1522, it is believed that he obtained an illegally imported copy of Martin Luther’s German Bible, which further fuelled his determination to translate the Bible into English. Like Luther, he condemned the Church and its preachers for the use of the Latin Scriptures to suit their purposes and in his “Obedience of the Christian Man”, published in October 1528, he said “they tell you that the scripture ought not to be in the mother tongue, but it is only because they fear the light, and desire to lead you blindfold and in captivity………but if the curates will not teach the Gospel, the layman must have the scripture, and read it for himself, taking God for his teacher”. At a confrontation with a learned member of the clergy who in defence of the church asserted that “we had better be without God’s laws than the Pope’s” William responded “I defy the Pope, and all his laws; and if God spares my life, ere many years, I will cause the boy that driveth the plough to know more of the scriptures than thou dost”.

In 1523 William left for London to seek permission to translate the Bible into English. He sought the help of Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, a well-known classicist who had worked, together with Erasmus, on a New Greek testament. The Bishop, however, was suspicious of William’s theology and un- comfortable with the idea of the Bible in the vernacular, and although in 1362, English had become the official language in Parliament and the Law Courts, the Church at this time forbad any English translation of the Scriptures.

William preached and worked on his translation in London for some time, relying on the financial help and board of a cloth merchant, Humphrey Monmouth. In the Spring of 1524, in the knowledge that his hoped-for printing in England was forbidden, he left for Hamburg, travelling on to Wittenberg where his name was entered in the matriculation registers of Wittenberg University and where, it is believed, he met Martin Luther. Here he worked on his translation of the New Testament, completing it in 1525. It was not until 1526 that a full edition of the New Testament was printed at Worms, an imperial free city then in the process of adopting Lutheranism. More copies were soon printed in Amsterdam. The book was smuggled into England and Scotland, most probably in bales of cloth and other goods, and was condemned by Bishop Tunstall who issued warnings to book sellers and had copies burned in public. Cardinal Wolsey condemned William as a heretic, and he was first mentioned in open court as a heretic in 1529. William remained in Antwerp for a period before going into hiding in Hamburg at around the same year, 1529. There he revised his New Testament and began translation of the Old Testament.

In England, with the growing threat of Protestantism to the established Church, the Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas More, fanatical in his pursuit and execution of so-called heretics (his letters published at the time condemning in vitriolic terms both Martin Luther and William Tyndale), saw to it that five of William’s supporters were burned at the stake. Before he became Chancellor in 1529, there had been few burnings of heretics in England. He soon put a stop to that, and it is said that at his property in Chelsea, there were stocks and a whipping tree used for the extraction of confessions of heresy. His writings express his joy at condemning his victims not only to the “short fire” but to the everlasting fires of hell.

![]() In 1534 William moved to Antwerp to take refuge at the English House that had been given to English merchants by the city governors to encourage trade, and where he was protected by the freedom from arbitrary arrest extended to its inhabitants. He was betrayed by a young man he had befriended, Henry Philips, who, short of money, was bribed by a person or persons unknown, but believed to have been the Bishop of London, Bishop Stokesley, Sir Thomas More or both, to discover his whereabouts. He was arrested and held in the Castle of Vilvoorde near Brussels. He was tried on a charge of heresy in August 1536 and was condemned to death, having been publicly degraded (stripped of his priesthood) beforehand. On about 6th October he is said to have been strangled to death at the stake and his body burned (an eyewitness recorded, however, that the executioner bungled the strangulation, and William was, in fact, burnt alive). His last words were reported to have been “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes”.

In 1534 William moved to Antwerp to take refuge at the English House that had been given to English merchants by the city governors to encourage trade, and where he was protected by the freedom from arbitrary arrest extended to its inhabitants. He was betrayed by a young man he had befriended, Henry Philips, who, short of money, was bribed by a person or persons unknown, but believed to have been the Bishop of London, Bishop Stokesley, Sir Thomas More or both, to discover his whereabouts. He was arrested and held in the Castle of Vilvoorde near Brussels. He was tried on a charge of heresy in August 1536 and was condemned to death, having been publicly degraded (stripped of his priesthood) beforehand. On about 6th October he is said to have been strangled to death at the stake and his body burned (an eyewitness recorded, however, that the executioner bungled the strangulation, and William was, in fact, burnt alive). His last words were reported to have been “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes”.

Unlike Erasmus and Luther who translated from the Latin Vulgate, Tyndale, an astonishingly gifted linguist, fluent in German, Italian, French, Spanish and importantly, Latin, Greek and Hebrew, translated his New Testament and Pentateuch from the Greek and Hebrew versions of the Bible. The latter two were more suited to his purpose, allowing more freedom of expression and his aim was to write in the plain English he grew up with in Gloucestershire, so that all, of whatever standing, would be able to read and under- stand the Scriptures. With his training in rhetoric at Oxford, and his acute sense of rhythm and poetry, he produced phrases of great beauty, many of which are in common use today, such as “twinkling of an eye”, “a law unto themselves”, “the powers that be”, “the salt of the earth”, “the signs of the times”, “the spirit is willing”, and “gave up the ghost”, to name but a few – not to mention the Lord’s Prayer which has come to us from Tyndale’s translation. Scholars believe that he contributed more to the English language than did Shakespeare.

William Tyndale gave us our English Bible. Within four years of his death three English translations of the Bible were published in England. After Tyndale’s arrest, a friend and colleague, Miles Coverdale, completed his Old Testament, his being the first complete bible to be printed. This was followed by what’s known as the “Matthew Bible”, Matthew being the pseudonym of John Rogers whose version, mostly comprised of Tyndale’s work, was published in 1537. And most significantly, at the behest of the King, Henry VIII, the Great Bible in English was printed for distribution to the churches in 1539. Bible scholars have concluded that in the King James Authorised version, which we have today, 83% of the New Testament and 76% of the Old Testament texts are Tyndale’s.

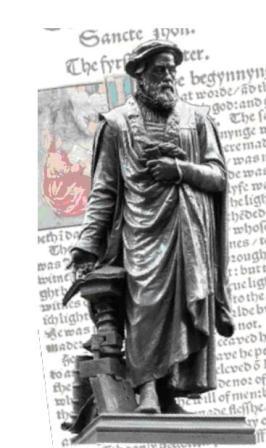

Tyndale Monument

Some three hundred years after William Tyndale’s death, and in the belief that he was born in North Nibley, the Tyndale Monument was erected on Nibley Knoll overlooking the village and the Vale of Berkeley. The foundation stone was laid on 29th May 1863 by the Hon. Colonel Berkeley and was finally inaugurated by the Earl of Ducie on 6th November 1866. A fitting memorial to a truly extraordinary son of Gloucestershire.

References:

David Daniell - ‘William Tyndale – a Biography’ (Yale University Press – 1994)

Brian Moynahan – ‘Book of Fire – William Tyndale, Thomas More and the Bloody Birth of the English Bible’ - (2nd Edition, Abacus 2010)

Timeline – History of the English Bible.

The Historical Society

If you are interested in local or family history and want to meet others with similar interests, The Historical Society and Heritage Centre is the organisation to join. By becoming a member you will also be able to attend our lectures as well as participate in the many social events, excursions and other activities we sponsor throughout the year. In addition you will receive our annual journal and newsletters.

Please visit the Society page to find out more.